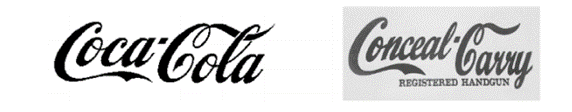

If you were The Coca-Cola Company (“TCCC”), how would you stop a trademark application for CONCEAL-CARRY REGISTERED HANDGUN (“CONCEAL-CARRY”) for clothing? The marks certainly don’t sound very similar. What if I told you the CONCEAL-CARRY application was filed in this stylization – would that change your mind?

Of course, it would! But why? For starters, COCA-COLA owns a registered trademark protecting the stylization for COCA-COLA that looks like this:

In addition to the protection of the words COCA-COLA, that also means that the way in which the words are presented – in a special font, with the exaggerated capital “C”s and the extended tails of the “C”s – that special stylization, known as the “Coca-Cola Script” is also protected and has been in use since the 1880s. We all instantly recognize this logo and especially the font. We would be able to identify it and associate it with soda and related goods no matter what it said. That is what makes the Coca-Cola brand not only valuable but also iconic.

Earlier this week, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) held that TCCC’s Coca-Cola Script mark is a famous trademark and refused to register the mark CONCEAL-CARRY (also in the Coca-Cola Script) for clothing goods. TCCC expertly argued that its Coca-Cola Script mark is not only a famous trademark that has been in use in commerce since the 1880s but also that the mark is iconic. The opinion is a fascinating read of how to properly counsel your clients to keep historical records of their use and it applies equally to small businesses as well as large brand owners. In the Trademarkabilities Masterclass, we teach our attorneys to always protect their client’s brands in standard characters as a first priority. Many business owners who file on their own ironically file for a stylized mark, which is usually not the best strategy in most cases. When a stylization is so iconic like the Coca-Cola Script, that is a mark that makes sense to protect as a stylization.

Prior Cases Finding the Coca-Cola Script Famous

For a trademark to be famous, it must be determined to be famous by a court or the TTAB. A famous trademark is one that has an immediate connection in the minds of the consumers with a specific product or service as to the source of its goods or services. If you saw any other words written in the Coca-Cola Script, wouldn’t it conjure up TCCC’s soda products in your mind? In fact, in the 1970s, TCCC enjoined a company from commercially selling, printing, or distributing posters with the phrase “Enjoy Cocaine” on them in the Coca-Cola Script. See Coca-Cola Co. v. Gemini Rising, Inc., 346 F. Supp. 1183, 175 USPQ 56, 57-58 (E.D.N.Y. 1972) due to the likelihood that consumers would think that the posters would be attributed to TCCC.

In 1920, the United States Supreme Court found the Coca-Cola Script mark to be “well known to the community.” See Coca-Cola Co. v. Koke Co. of America, 254 U.S. 143 (1920). There are not many American brands that have such a history of distinguished decisions citing their marks as a part of the American culture dating back so many years. Famous trademarks enjoy a broad scope of protection, even beyond the scope of their goods and services, because of how well-known the marks are by the consuming public.

There are four non-exclusive factors a party must prove when it is alleging fame including:

- The duration, extent, and geographic reach of advertising and publicity of the mark;

- The amount, volume, and geographic extent of sales offered under the mark;

- The extent of actual recognition of the mark;

- Whether the mark was registered on the Principal Register.

In this case, applicant unsuccessfully argued that the COCA-COLA trademark cannot indefinitely be famous and that its strength is declining because younger generations do not recognize the COCA-COLA trademark. While some trademarks may fade over time, especially when market conditions change, there is no rule that says a savvy market leader cannot keep its market leadership position, especially since trademarks earn their value based on use in commerce. TCCC was able to submit evidence of its use from every decade since 1880 and specific sales and advertising figures, especially over the past five years. Anyone with an interest in trademark law should review this opinion for how to properly argue fame (and note that the same procedure would apply for acquired distinctiveness).

How the Coca-Cola Company Established Dilution

In this Opposition, TCCC was able to demonstrate that even though the mark CONCEAL-CARRY in a stylized format and the Coca-Cola Script are not highly related from a likelihood of confusion analysis, there is a high degree of similarity in the appearance of the marks meant to conjure up the famous Coca-Cola Script mark. The Board found that both marks both contain two words that both begin with the letter “C” and that both words have capital “C”s. In addition, applicant’s mark uses two 2-syllable words just like the Coca-Cola mark and that the treatment of the script is identical to that of the Coca-Cola script. The comparison of the two marks by the Board on page 39 of the opinion may be of interest to trademark attorneys to review. In using the mark, applicant planned to use the mark in white against a red background – a color treatment most readily identifiable with Coca-Cola’s trade dress, and applicant included “Registered Handgun” as a part of the mark’s stylization which the Board found to mimic TCCC’s inclusion of “Registered Trademark” underneath its marks on its bottles and packaging. Although the application was filed on an intent to use basis, there had been few if any sales. The Board held that there was “no doubt that the [a]pplicant intended to associate his mark with the Coca-Cola Script [m]ark [and that] the factors collectively strongly support a finding of the likelihood of dilution by blurring.”

Conclusion

It is exceedingly difficult to prove that a brand is famous and few of us will be involved in such a case. If we are, this case is a textbook example of how to prove fame and how to counsel your client through such a process if they believe they have a mark that might meet the fame factors. For any such brand owners, they must also spend a significant amount of financial resources to defend their famous marks to ensure their investments are safe from third- party infringers.

Stacey C. Kalamaras is the founder and lead instructor of Trademarkabilities®, an online trademark academy for lawyers, whose mission it is to prepare lawyers to be confident and effective practitioners before the USPTO. Stacey started Trademarkabilities to share her passion teaching the law with the next generation of lawyers and help them become practice ready lawyers. Contact us at: hello@trademarkabilities.com.

Stacey is also a seasoned trademark attorney and currently works in-house as Senior Counsel for a multi-national candy company. She previously owned her own solo trademark practice, which she scaled and sold. She has been recognized by her peers for her outstanding knowledge and service in intellectual property law.